World Climate with Chinese Officials

By

Ellie Johnston

July 2, 2012

Guest post from Professor John Sterman:

Guest post from Professor John Sterman:

I recently ran the World Climate role play negotiation with a group of about 30 officials from China, as part of the IDEAS/China program run here at MIT Sloan by Otto Scharmer, with the help of Peter Senge and Joe Hsueh (a recent graduate of our doctoral program in system dynamics). We ran the session using simultaneous interpretation, with two professional interpreters and Joe’s help.

Most of the participants were provincial or municipal officials from Zhejiang province (near Hangzhou), along with some business leaders from the region and a few academics from Tsinghua University.

We ran the role play as we usually do, including: food for the delegations from the developed world, but bare tables for the participants playing the roles of the delegates from China, India and the Other Developing Nations; having the Other Developing Nation representatives sit on the floor; covering them with the blue tarp when sea level rose, and so on. Overall it seemed to go very well, with the simultaneous translation only slowing things down slightly.

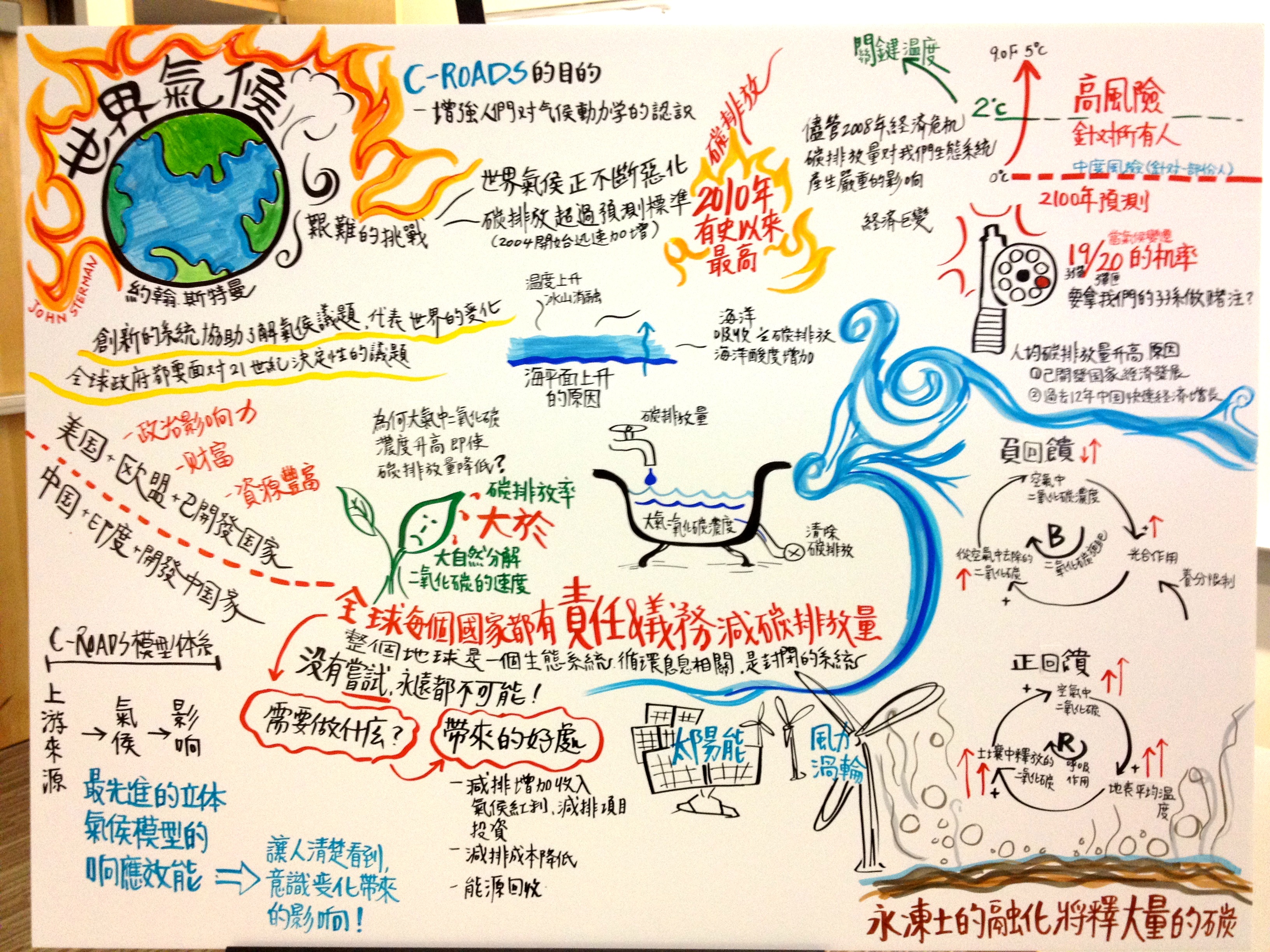

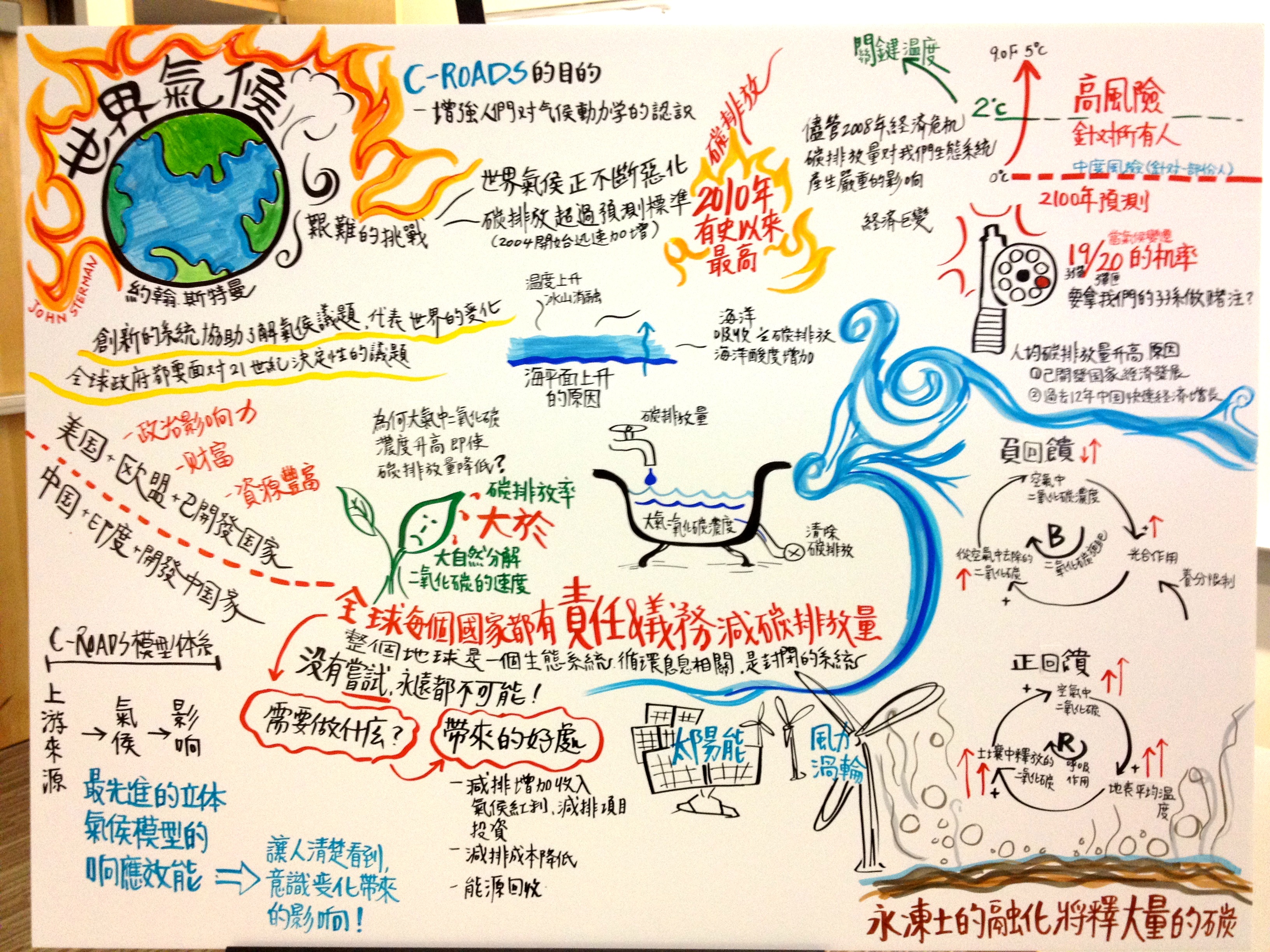

I have included a slide with the first round of proposals they made, and a picture of the graphic record of the session, in Chinese. Interestingly, they made larger and earlier commitments to cuts in emissions from all the developed nations than is typical with Western participants, with much later, smaller cuts from the rest of the world (perhaps not surprising). Even in the first round, though, the Chinese delegation was willing to commit to ending Chinese emissions growth in 2050 and beginning a decline, of 1%/year, in 2070. Using C-ROADS we then saw the impacts of these commitments on the climate, including GHG concentrations, global mean temperatures, ocean pH and sea level rise. Under their first round proposals, sea level by 2100 rose by 1.5-2 meters, depending on how sensitive the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets are to rising temperatures. Sea level would continue to rise long after 2100 of course, and, though the ultimate increase is highly uncertain, the magnitude could be meters more. I then showed them the impact of such sea level rise on China using flood.firetree.net. This useful site allows you to zoom in on any part of the world and see the impact of different amounts of sea level rise. The participants were surprised, even shocked, to see that with just 2m of sea level rise most of Shanghai and much of Zhejiang province would be inundated. They asked to see other parts of the Chinese coast, particularly the economic powerhouse in Guangzhou province, including Shenzen. Most of this economically vital region of China would also be lost to just 2m of sea level rise. We then looked at the impact of sea level rise on geopolitical hotspots in Asia such as the Indus delta, where sea level rise will displace millions of people, and they had a lively discussion of the risks to China arising from conflict on their borders between India and Pakistan, both of which possess nuclear weapons. Being able to connect emissions policies to impacts on China made a big impression on the group. Until they saw the results of their own proposals, I don’t think they understood how climate change would hurt China.

I have included a slide with the first round of proposals they made, and a picture of the graphic record of the session, in Chinese. Interestingly, they made larger and earlier commitments to cuts in emissions from all the developed nations than is typical with Western participants, with much later, smaller cuts from the rest of the world (perhaps not surprising). Even in the first round, though, the Chinese delegation was willing to commit to ending Chinese emissions growth in 2050 and beginning a decline, of 1%/year, in 2070. Using C-ROADS we then saw the impacts of these commitments on the climate, including GHG concentrations, global mean temperatures, ocean pH and sea level rise. Under their first round proposals, sea level by 2100 rose by 1.5-2 meters, depending on how sensitive the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets are to rising temperatures. Sea level would continue to rise long after 2100 of course, and, though the ultimate increase is highly uncertain, the magnitude could be meters more. I then showed them the impact of such sea level rise on China using flood.firetree.net. This useful site allows you to zoom in on any part of the world and see the impact of different amounts of sea level rise. The participants were surprised, even shocked, to see that with just 2m of sea level rise most of Shanghai and much of Zhejiang province would be inundated. They asked to see other parts of the Chinese coast, particularly the economic powerhouse in Guangzhou province, including Shenzen. Most of this economically vital region of China would also be lost to just 2m of sea level rise. We then looked at the impact of sea level rise on geopolitical hotspots in Asia such as the Indus delta, where sea level rise will displace millions of people, and they had a lively discussion of the risks to China arising from conflict on their borders between India and Pakistan, both of which possess nuclear weapons. Being able to connect emissions policies to impacts on China made a big impression on the group. Until they saw the results of their own proposals, I don’t think they understood how climate change would hurt China.

Nevertheless, in the first round debrief some participants emphasized the usual argument we hear that ‘the west created the problem, the west must solve it.’ I then ran a hypothetical case in which GHG emissions from all developed nations fall to zero immediately, today, while keeping their first round proposals for China, India, and the other developing nations as they were. The participants saw for themselves that China, India and the developing world would still suffer immensely. This was surprising to them. Digging into the model, they saw that the projected growth in emissions from their own nations become so large that global temperatures continue to rise, leading to harmful impacts on agriculture, water availability, the oceans and sea level. It’s true that most of the emissions to date came from the developed nations, and there can be no solution to the challenge of climate change unless these developed nations make substantial cuts in their emissions, as early as possible. But it’s also true that dramatic cuts in the west aren’t enough: to protect their own interests in a prosperous future, China, India and the developing nations must also build a low carbon economy and cut their own GHG emissions.

In the next round, the delegates proposed much larger emission cuts for China, India, and the other developing nations — but only after they persuaded the delegates from the developed world to commit to much larger financing — ending with about $150 billion/year to aid the least developed countries (China would not commit, arguing that they would be spending huge sums to transform their own country to a low carbon economy — fair enough, I suppose). Although it’s not realistic, their final policies stabilized CO2 concentrations by 2100 and led to a change in temperature only slightly above 2° C. It was quite impressive. We then talked about feasibility. I’m sure many of them are still skeptical, but there were many interesting comments about ‘seeing the long-term common interests of all nations’ and ‘investing today to protect China tomorrow’.

Using the model to show the impact of cutting the west’s emissions to zero now and seeing that China (and India and all others) would still be harmed — that the developed economies can’t do it alone — had a large impact. It was also clearly helpful that they’d had several days already of exposure to systems thinking and to Otto’s U process, so they were sensitized to ideas like creative tension, feedback, mindfulness, and being present with their authentic selves. In the final reflection session, in a large circle, they spoke about their aspirations and vision for a healthy, prosperous and safe world, with less denial, resistance and fear than is typical.

As part of the workshop prep we had my World Climate slides, the briefing memos for the delegations, and the proposal form translated into Chinese. These materials are posted among the Facilitator’s Resources in the World Climate section of the Climate Interactive site as an additional resource for those who may wish to run the model in Chinese.

John D. Sterman is the Jay W. Forrester Professor of Management at the MIT Sloan School of Management and Director of MIT’s System Dynamics Group. His research includes systems thinking and organizational learning, computer simulation of complex systems, climate change and sustainability.