COP21: Inaction or momentum for change?

By

Shanna Edberg

December 9, 2015

Cross-post from the University of Massachusetts Lowell Climate Change Initiative by Juliette Rooney-Varga, World Climate facilitator and researcher

The Twenty First Conference of Parties (COP21) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change is by far the largest and perhaps the most important COP thus far. Unprecedented in scale and approach, COP21 is a product of more than two decades of UN climate negotiations (and its failures) as well as a civil society conference that has emerged from the negotiations and now literally surrounds them. COP21 attracted over 40,000 participants, including a staggering diversity of peoples, disciplinary expertise, societal sectors, and even ages. I spent the first week of the conference representing the UMass Lowell Climate Change Intiative and joining our partners at Climate Interactive, a small U.S.-based NGO working to bridge the gap between climate change science and policy.

Despite the negotiations’ snail-paced wrangling, there was a real sense of momentum for change outside the plenary halls.

Despite the negotiations’ snail-paced wrangling, there was a real sense of momentum for change outside the plenary halls.

Is success possible?

The failure of prior UN climate negotiations to deliver meaningful agreements and the certain refusal of the U.S. Senate to ratify a binding climate treaty initiated a new approach at COP21: submission of “Intended Nationally Determined Contributions” (INDCs), or emissions pledges by each country, mostly well in advance of the conference. Thus, rather than arguing about who should do what, countries came to the table with their pledges already known. Other changes included kick-starting the conference with a historical meeting of heads-of-state and adding side meetings with small groups of negotiators tasked with ironing out a paragraph at a time to try to avoid plenary gridlock over specific language. Despite these attempts to smooth a road to success, one week into the conference, there is still a fear that negotiators will fail to reach agreement on key components of the text, ranging from purpose (i.e., what, if any, temperature rise goal will be included) to process (i.e., when, how, and by whom, if at all, will pledges be strengthened and progress monitored and verified).

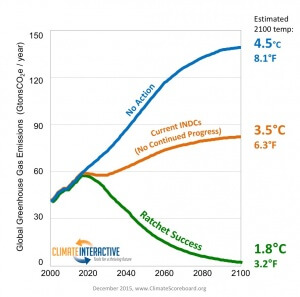

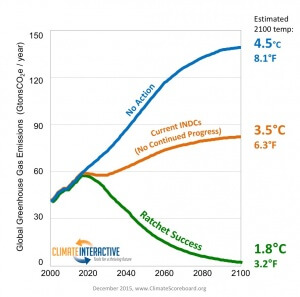

The gap between INDCs and “Ratchet Success” pathways.

The gap between INDCs and “Ratchet Success” pathways.

On the first day of COP21, the Climate Interactive team released their analysis of the INDCs, along with a “Ratchet Success” scenario that would be likely to deliver <+2 ˚C by 2100 (see figure). While the INDCs are far from sufficient, if they are both implemented as promised and aggressively ratcheted within a five-year review period, they could keep a pathway to the 2 ˚C goal open. Throughout the week, our conversations focused on what could be done, both at and beyond COP21, to communicate a meaningful “Ratchet Success” scenario and help bridge the gap between pledged and needed action.

Especially given the inadequacy of the INDCs, it was fascinating to hear from representatives of about 120 countries who are calling for a much more ambitious goal of limiting warming to <1.5˚C. This goal is considered by many scientists to be out of reach, as it would call for immediate action at an unprecedented scale. Perhaps not surprisingly, member nations of the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) and the Pan-African Climate Justice Alliance, whose literal survival is at stake, are unsympathetic to wealthy nations’ claims that such action is not achievable. I’m sure that many of the youth participants would agree. Ultimately, this is the heart of what this conference is about: international and intergenerational justice.

Bridging the gaps

Local to global

Despite the failure of COPs to date, the inadequacy of the INDCs, and even the potential for a weak agreement emerging from Paris, progress has been made and looks likely to accelerate. Perhaps this was most evident on the civil society side of the conference, which achieved a new level of scale, coordination, and range of sub-national and non-state initiatives. I think this message is especially important for those of us from the U.S., where action at the national level is stymied by Congressional gridlock or, worse, active opposition. Indeed, the action taken by the private sector, states, cities, and institutions such as our own UMass Lowell, all at sub-national levels, are what make the U.S. INDC possible. So far, this work has not only demonstrated that aggressive action is possible, but it has also shown that such action can save money, create jobs, and improve public health, while also building the political will that may eventually move Congress. Whatever the final outcome of COP21 or indeed COP22, participating in a global event has certainly renewed my personal commitment to the local actions that I contribute to.

Science to policy

Climate change and all of its implications and players likely represent one of the most complex and difficult challenges faced by humanity. When considering stated temperature goals (i.e., <1.5 or 2 ˚C warming), delegates working to develop a consensus agreement must not only consider what the biogeochemistry of the climate system demands, but also what they may or may not be able to demand from the other 195 countries they are working with to come to a consensus agreement. Answers to such questions are not quick, back-of-the-envelope calculations, but rather an application of current scientific understanding and assumptions to a multitude of what-if scenarios. It is simply not feasible to expect negotiators to somehow discern what the geophysical implications of their individual decisions are. They are clearly already overwhelmed by the complexity of 196 countries attempting to come to a consensus decision on every word of ~50-page document.

Meanwhile, scientists are neither trained nor incentivized to deliver rapid (i.e., immediate) feedback to delegates about various policy scenarios (generating the data for and publishing a peer-reviewed scientific paper is a process that typically requires more than a year). Thus, there is an urgent need for a new approach that brings science and policy together, distilling the key points from the confusion in order to inform a process that at least has a chance of meeting our stated international goals.

Frank Niepold (Climate Education Coordinator for the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and U.S. Global Change Research Program; member of the U.S. Delegation) sharing Climate Interactive’s INDC and Ratchet Success scenarios as part of the #Youth4Climate international education initiative at COP21.

Frank Niepold (Climate Education Coordinator for the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and U.S. Global Change Research Program; member of the U.S. Delegation) sharing Climate Interactive’s INDC and Ratchet Success scenarios as part of the #Youth4Climate international education initiative at COP21.

Through a collaborative effort between Climate Interactive, MIT, Ventana Systems, and the UMass Lowell Climate Change Initiative, we have developed decision-support computer simulations that are designed to bring current scientific understanding to the policymaking process without the time delays inherent in most scientific analyses. Yet even with these policy-oriented decision-support simulations, the questions and answers are not straightforward. It was an honor to be a part of the team’s conversations throughout week one of COP21, as they fielded a barrage of questions from top journalists, such as:

- What will the INDCs deliver (note that INDCs continued to filter in throughout the first week of COP21)?

- Is it still possible to achieve a <1.5 ˚C or 2 ˚C outcome? If yes, who would need to do what?

- Does it make a difference if INDCs are reviewed and ratcheted in five years or ten years?

If one considers these questions from the perspective of a delegate representing one out of 196 countries, the answers become much more complex – i.e., given the context of what global biogeochemistry demands (which they may or may not understand) what is in the best of interest of my own country?

Clarity to confusion

My own contribution to COP21 was directly tied to the National Science Foundation-funded project I lead, in collaboration with Climate Interactive and SageFox Consulting Group, to develop and research simulation-based role-playing exercises that deliver key insights into the climate and energy systems. The gap between the INDCs and “Ratchet Success” make the need for transformational education clear: whether through action to address the climate challenge or through the impacts that will result from our failure to do so, climate change will play a major role in the lives of people who are young today.

Running World Climate, the mock UN climate negotiations, meters away from the real UN climate negotiations. The Associated Press and ABC News covered the event.

Running World Climate, the mock UN climate negotiations, meters away from the real UN climate negotiations. The Associated Press and ABC News covered the event.

We are working to bring the complexity of both the science of climate change and the social dynamics of decision-making to students, youth groups, citizens, business leaders, academic institutions, and even policymakers around the world. Our approach is simple: we have created World Climate, a mock UN climate negotiation exercise that is framed by the same decision-support simulation used to provide rapid feedback to the real negotiations. Participants take on the roles of delegates and are challenged to create a global deal that meets the <2 ˚C goal according to the best available science. We ran World Climate during COP21, meters away from the real negotiations (in fact, an official interrupted us and asked us to be quieter because the French minister was working next door) and the event was apparently just as interesting – it was covered by ABC News and the Associated Press. Also during COP21, and as part of the White House’s Climate Literacy Initiative, we were thrilled to announce that we had met our goal of reaching over 10,000 participants in 46 countries during 2015 alone. As I look ahead to further growth of this project, I hope that the young people that we reach, no matter what their interests and future careers, will be better equipped to understand complex problems, cross silos, and address the challenges we face. As an educator, a scientist, and a mother, that is one contribution I hope to make to help bridge the gap.

Despite the negotiations’ snail-paced wrangling, there was a real sense of momentum for change outside the plenary halls.

Despite the negotiations’ snail-paced wrangling, there was a real sense of momentum for change outside the plenary halls.

Frank Niepold (Climate Education Coordinator for the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and U.S. Global Change Research Program; member of the U.S. Delegation) sharing Climate Interactive’s INDC and Ratchet Success scenarios as part of the #Youth4Climate international education initiative at COP21.

Frank Niepold (Climate Education Coordinator for the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and U.S. Global Change Research Program; member of the U.S. Delegation) sharing Climate Interactive’s INDC and Ratchet Success scenarios as part of the #Youth4Climate international education initiative at COP21. Running World Climate, the mock UN climate negotiations, meters away from the real UN climate negotiations. The Associated Press and ABC News covered the event.

Running World Climate, the mock UN climate negotiations, meters away from the real UN climate negotiations. The Associated Press and ABC News covered the event.